If you’ve traveled to Japan or watched Japanese films and literature, you’ll likely recognize Jizo as a popular and iconic figure. Jizo is a Buddha in Buddhism, and in Japan, he’s often depicted in a kawaii and cute form, resembling a small child with a gentle smile.

Many streets in Japan feature small stone statues of Jizo, with almost every neighborhood having at least one. For those familiar with Japanese movies and anime, Jizo holds significant cultural importance, often appearing in scenes with a sense of warmth and protection.

As children, many Japanese were warned by their elders not to disturb Jizo statues, as it was believed that misbehaving could lead to misfortune. This reflects the deep respect and reverence Japanese people have for Jizo, symbolizing protection for children, travelers, and the deceased. This cultural reverence remains still strong In Japan now .

In today’s article, let’s dive deeper into Japanese Jizo culture and uncover the story behind this beloved figure.

Jizo is directly associated with the bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha, who is said to vow not to attain Buddhahood until all beings in hell have been saved. As the embodiment of this vow, Jizo’s role in Buddhism focuses on compassion, offering guidance, and alleviating suffering for those in need. In particular, he is seen as the compassionate protector of souls, especially children who have passed away, as well as travelers embarking on dangerous journeys.

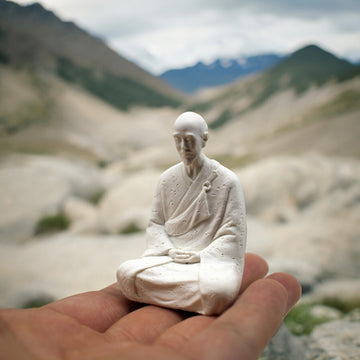

Jizo is often depicted as a smiling, childlike figure, embodying warmth, compassion, and protection. His cheerful, approachable appearance reflects his deep desire to provide solace to all who are suffering or in need of guidance. For many, Jizo represents a comforting figure to turn to during difficult times, especially in the face of loss or uncertainty.

You can often find Jizo statues adorning streets across Japan, offering protection and blessings to travelers and locals alike.

In rural Japan, Jizo statues are frequently found along roadsides, in cemeteries, or near temples, serving as guardians for local communities. He is often seen as a symbol of hope and security for the most vulnerable members of society, including children and those who are lost or in peril.

The origins of Jizo trace back to early Buddhist traditions and its introduction to Japan around the 8th century. Records from the Nara period, such as the Jūrin-kyō (Ten Wheels Sutra), describe Jizo as a bodhisattva sent by Buddha Shakyamuni to care for humanity. Initially, there was little evidence of widespread devotion to Jizo. However, by the early Heian period (794–1185), declining aristocratic families began seeking Jizo’s blessings for protection and solace.

Jizo's role further evolved during the Edo period, when he became widely venerated as the protector of children. During that time, infant mortality rates were alarmingly high. Legend tells of children who died young being sent to Sai no Kawara, a liminal riverbank where they were forced to stack stones as penance for causing grief to their parents. Jizo was believed to rescue these children from torment, guiding them to peace.

Red bibs and hoods are offerings to Jizo, symbolizing prayers for protection. Their childlike appearance reflects Jizo’s role as a guardian of children and a symbol of care.

This belief gave rise to rituals like dressing Jizo statues in red bibs and hats, symbolizing protection and love for children.

In addition to child protection, traditions like "substitute Jizo" and "thorn-removing Jizo" symbolize Jizo’s role in bearing the physical or spiritual suffering of devotees. Famous temples, such as Tokyo’s Jōtokuzan and Sugamo’s Togenuki Jizo, are dedicated to these legends.

Even today, Jizo statues remain central in Japanese communities, with red garments representing vitality and life, while prayers to Jizo reflect enduring care for children and loved ones.

Jizo statues, a familiar sight across Japan, come in various styles and forms, each embodying specific aspects of Jizo’s compassionate nature. Some statues depict Jizo as a serene monk holding a staff (shakujo) and a jewel (hoju), symbolising guidance and fulfillment of wishes.

Others feature Jizo adorned with red bibs and hats, offerings from devotees praying for protection or expressing gratitude. These variations showcase Jizo’s adaptability to diverse needs and beliefs.

Different types of Jizo statues serve unique purposes, reflecting their protective roles. For instance, child-protecting Jizo (Kodomo Jizo) often appear near residential areas, symbolising the guardian of children.

Traveler-protecting Jizo (Rokujizo) are placed along roads and mountain paths to ensure safe journeys, while soul-guiding Jizo (Mizuko Jizo) are commonly found in cemeteries, offering comfort to departed souls. Each type highlights Jizo’s connection to specific aspects of human life and suffering.

The classic image of Jizo in Japan features a staff, symbolizing guidance, protection, and the power to ward off evil.

Jizo statues are strategically located in a variety of settings. Temples often house intricately crafted Jizo figures as focal points of worship. Roadsides and rural paths feature simple stone Jizo statues, acting as silent protectors for passersby. Cemeteries frequently host Jizo statues as spiritual guides, bridging the gap between the living and the deceased.

Iconography plays a significant role in Jizo’s representation. The shakujo staff wards off evil spirits, while the hoju jewel grants wishes and dispels darkness.

Jizo’s monk-like simplicity and childlike smile radiate compassion, making these statues relatable symbols of hope and protection. The addition of red garments further emphasises life, warmth, and connection to children in Japanese cultural belief.

Jizo has been a prominent figure in traditional Japanese art for centuries, often depicted in woodblock prints and sculptures. These artworks commonly portray Jizo in a serene and compassionate pose, wearing traditional Buddhist robes and holding a staff or a jewel, symbols of guidance and protection.

Many ancient sculptures can be found in temples and shrines, where they serve as both a visual representation of the bodhisattva and a focal point for prayer and devotion.

Jizo is often shown with a gentle smile, evoking a sense of comfort and safety.

In modern times, Jizo’s image has also found its way into popular culture, including films, anime, and manga. One notable example is in the Doraemon short story, The Mischievous Jizo, where Doraemon accidentally travels back in time to ancient Japan and is mistaken for Jizo.

The story blends Japanese mythology with humor, showcasing how Jizo’s cultural significance continues to resonate with contemporary audiences.

The juxtaposition of traditional and modern representations reflects Jizo's enduring popularity and his role as both a protector and a cultural symbol in Japanese society.

Praying to Jizo is a deeply spiritual practice for many in Japan, with various rituals and prayers associated with this form of worship. One of the most common prayers is the Jizo Bosatsu Kōbutsu, a chant that calls upon the bodhisattva to offer protection and comfort.

Devotees may recite this prayer in front of a Jizo statue, asking for guidance, safety, or help for loved ones in need. The ritual often involves lighting incense, bowing, and offering words of devotion.

Offerings to Jizo are a significant part of the worship practice, often placed at Jizo statues in temples, cemeteries, or along roadsides. These offerings can include toys, particularly for children, clothing such as red bibs or hats, and even food items.

The red clothing, in particular, is symbolic of protection for children and is believed to shield them from harm. Many people, especially parents, offer these items to ask Jizo to watch over their children and bring them health and safety.

In Japan, Jizo plays a vital role in funeral rites and memorial services. As the protector of souls, Jizo is believed to guide the deceased through the afterlife and provide solace to grieving families. Many families pray to Jizo during the mourning period, offering prayers for their departed loved ones' peaceful passage.

To pray to Jizo for protection, guidance, or blessings, one can quietly sit or kneel before a statue, say their prayer aloud or in their heart, and make offerings. The belief is that Jizo listens with compassion and provides comfort to those in need.